The Bomber Offensive (Part 18) - Pattern Analysis: Targeting and Measures of Effectiveness

It is difficult to identify the optimal targeting approach if you cannot accurately measure the effectiveness of your targeting campaign.

Targeting: Challenge of Measuring Effectiveness

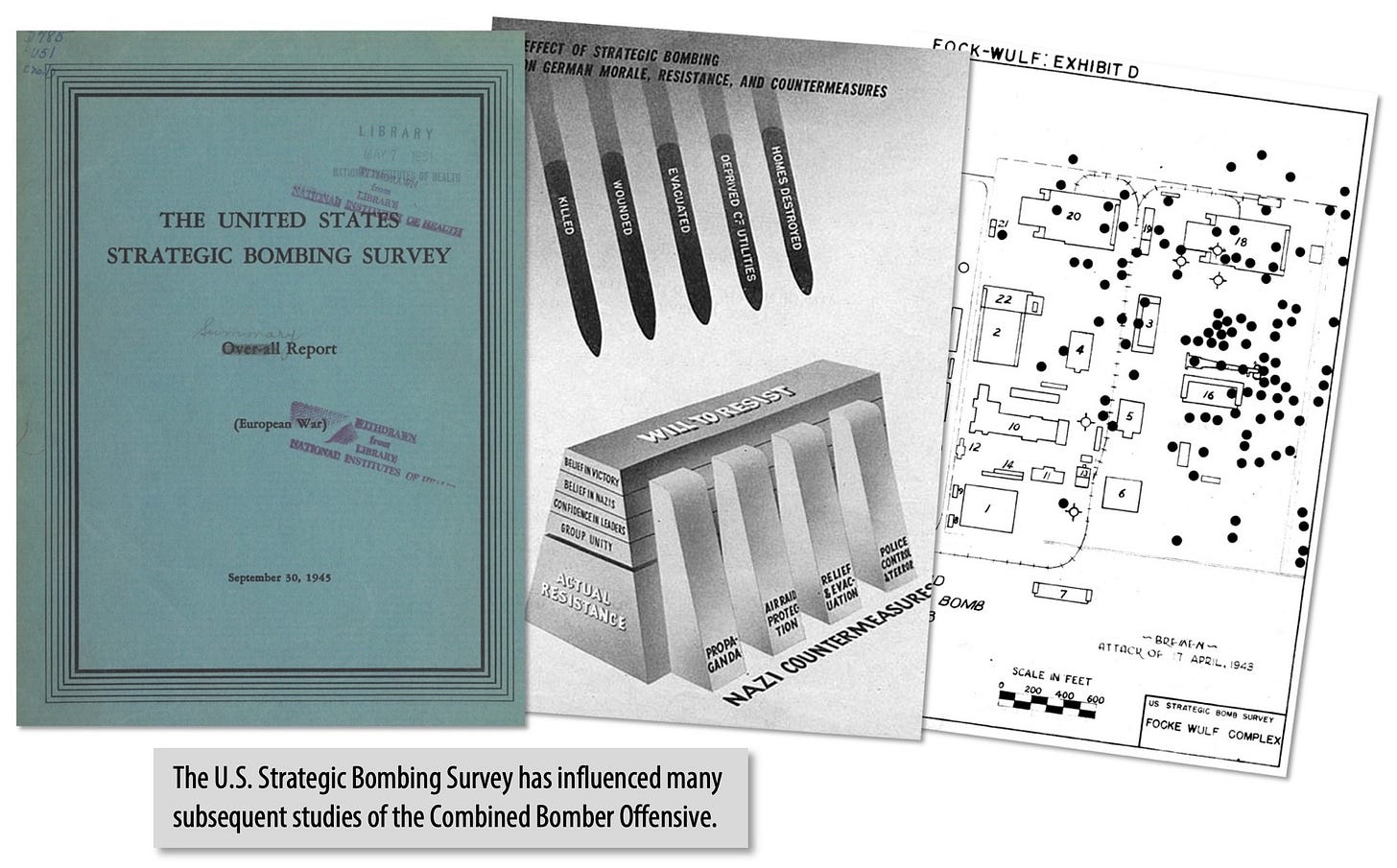

Over the years, studies of the Combined Bomber Offensive have been heavily influenced by the findings of the official U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. Studies to support this survey began in November of 1944 and have been discussed, expanded upon and argued about ever since. The survey addressed all four of the key elements we have discussed thus far: targeting, survivability, accuracy and bomb damage. However, the most controversial and influential components of the analysis focused on the targeting question. Which target choices were actually most effective and which, if any, contributed most to victory?

As many historians have pointed out, the Strategic Bombing Survey, along with much of the mainstream historical analysis, offer a seemingly negative evaluation of strategic bombing in World War II. While the precise criticisms vary from author to author, the only point that could be considered universal and irrefutable was that strategic bombing did not achieve the results it claimed it could achieve based on interwar and early war analysis. In short, many overzealous proponents of air power believed that strategic bombing could bring an end to the war, either by itself or as the main contributing factor in the larger war effort. The Strategic Bombing Survey and subsequent analysis proves this did not in fact happen.

Strategic bombing was not solely responsible for victory in World War II and is likely not the single most critical factor leading to victory. At various points in the war, such as during the RAF’s Berlin campaign or the USAAF’s oil campaign, leaders believed that a series of raids could clinch an early victory if only enough pressure and effort were applied. This never proved to be the case. However, while strategic bombing failed to achieve the lofty goals it had set for itself, that is not to say it was ineffective or that it did not make a significant contribution to victory.

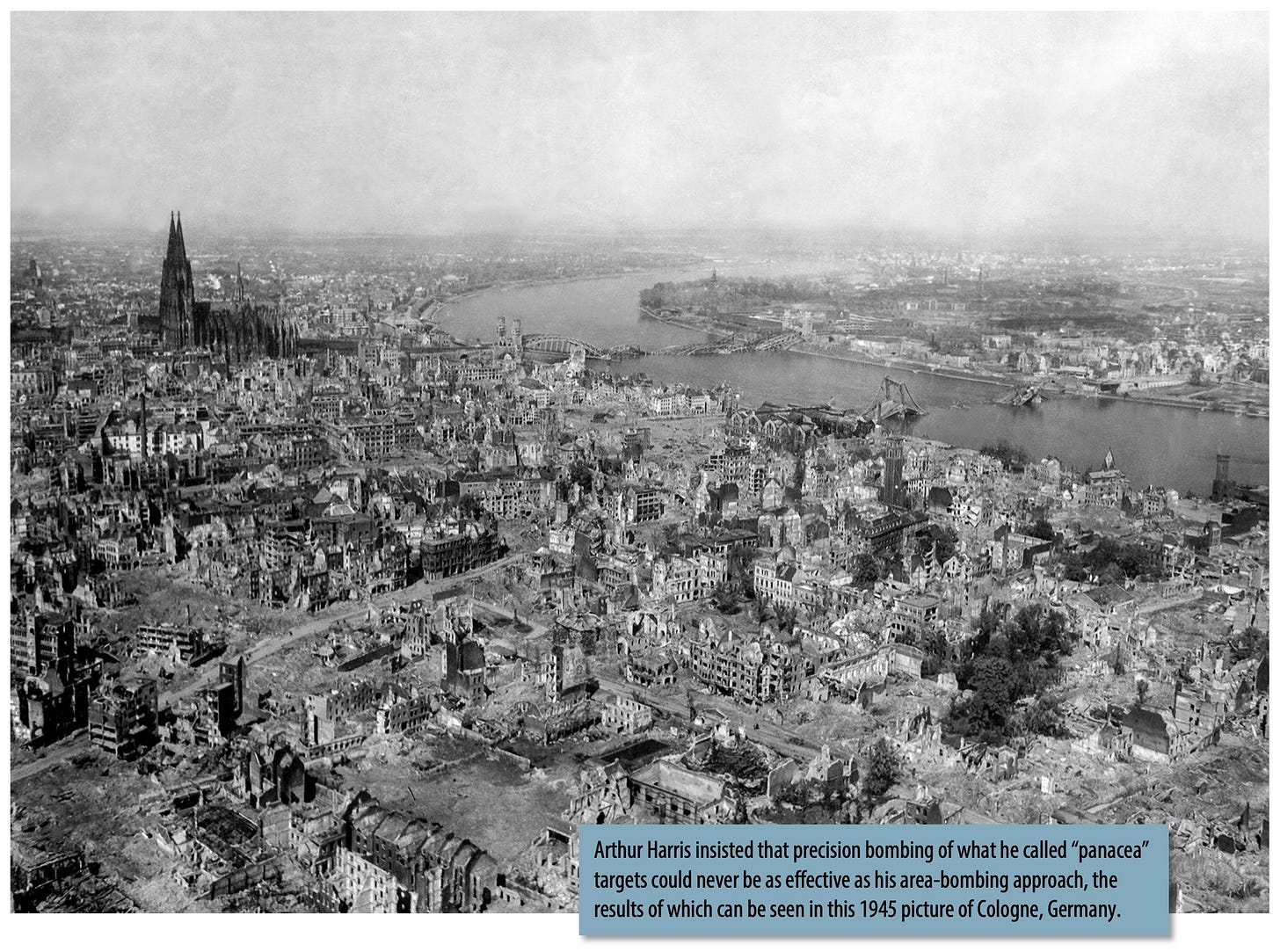

Given these points, a more nuanced analytical question would be to ask which targeting efforts proved to be the most effective in comparison with the others. While this is an interesting and important question, answering it can be very difficult. Advocates for Harris’ area bombing approach can point to comments from Albert Speer following the devastating bombing of Hamburg, asserting that a continued succession of similar raids would shut down German arms production. Supporters of the Oil plan might claim that Spaatz’ efforts ultimately did “end the war” and once the USAAF started targeting oil, the German economy did in fact grind to a halt. Advocates of the Transportation Plan might retort that the collapse of the German economy was at least equally the result of Tedder’s campaign in September of 1944.

The problem with determining who is correct in such arguments is that there are countless variables at work and there is often no way to directly link cause to effect. Did the Germany economy collapse because of the Oil Plan and Transportation Plan or was it on the verge of collapse anyway? Analysts who seek to marginalize the contributions of the Combined Bomber Offensive sometimes point to the fact that actions on the Eastern Front were far more significant in terms of overall damage to the German war effort. However, would the war on the Eastern Front have looked much different had there been no Combined Bomber Offensive?

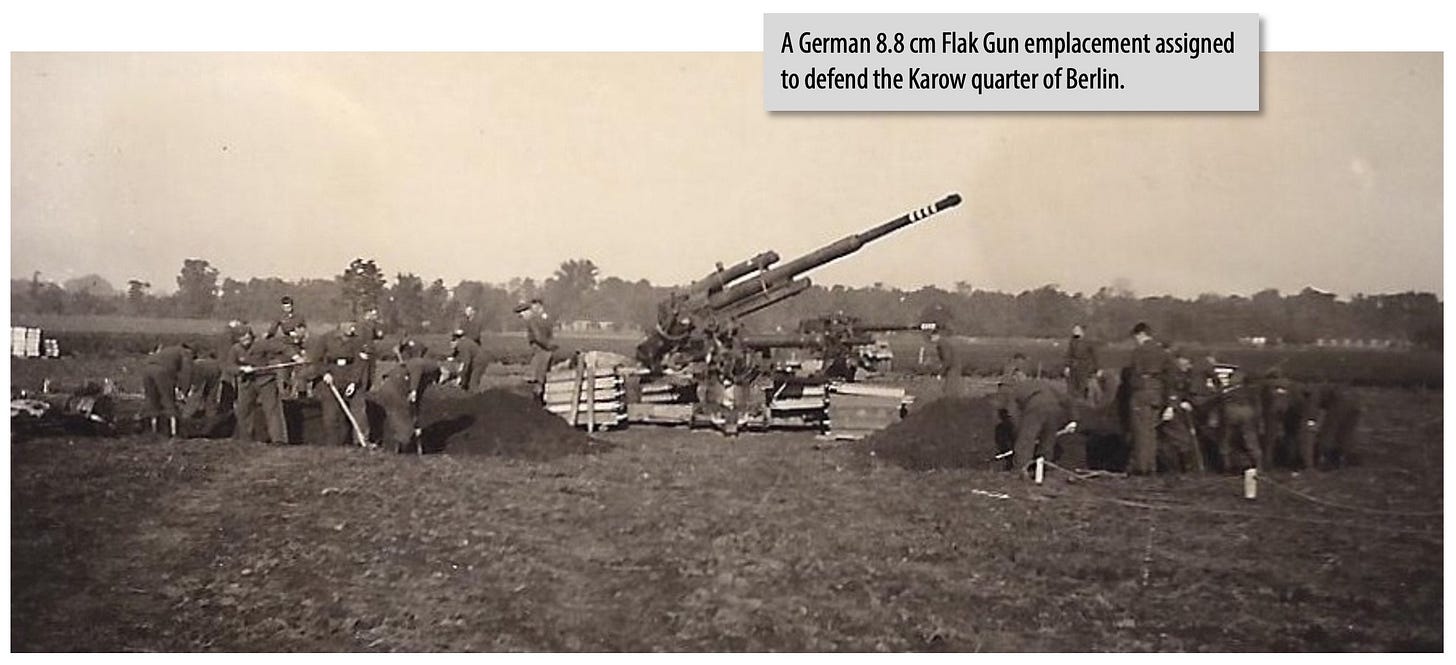

Some often-cited points include the fact that at various times during the war, more than 50,000 anti-aircraft guns were assigned to defend against Allied bombing. Most notably, the majority of Germany’s feared 88mm Guns were assigned to defend against bombers. Given that the 88’s were perhaps even more effective in the anti-tank role than they were against aircraft, what might have happened if all of these guns had been available on the Eastern Front? Would the Russians have been able to win without the help of critical supplies and reinforcements delivered from the United States across the North Atlantic? Would such convoys have continued to come if Allied aircraft had not helped suppress the U-Boat threat?

The endless string of potential questions and interrelated variables makes it difficult to label any single effort in the Combined Bomber Offensive as effective or ineffective. The questions themselves are also not straightforward. If the decision were made to divert the 88mm guns defending the Reich to the Eastern or Western fronts for use against tanks, finding the additional vehicles and fuel to transport them would not have been easy. The fact that the Wehrmacht relied heavily on horse transportation and that the 88mm gun was too heavy for horses to pull in most situations further complicates the real-world application of this counter-factual scenario. However, regardless of the specifics, the general principle that the Combined Bomber Offensive diverted resources and attention away from other fronts is indisputable.

These are just a few examples of how analytical questions can descend into fascinating but never-ending spirals. Respected historians who have studied the Combined Bomber Offensive for many years still cannot agree about the overall effectiveness of the effort or about which individual targeting campaign (area bombing, oil or transportation etc.) made the most important contribution. However, in the confusing search for a definitive analytical conclusion to the targeting question we can overlook the more relevant conclusion that is staring us in the face.

One of the most critical lessons of the Combined Bomber Offensive is proven by the very fact that no one can agree on the targeting analysis, even with the benefit of hindsight and access to an unprecedented number of records and data on both sides. What does this mean for the military professional or planner who is in the process of executing an air campaign and is trying to make targeting decisions? Success in targeting requires accurate bomb damage assessment and well-designed measures of effectiveness. Otherwise, there is no way to know whether your efforts are having a positive effect or not.

While technologies and sensors do exist today that could potentially make damage assessment and measures of effectiveness more accurate, it is unlikely that real-time battlefield data will ever be as detailed as the historical information available to scholars. In addition, given the youth of such technologies, little past performance is available when trying to assess how accurate modern data could be. Even if the data itself is flawless, it will still be difficult to establish definite causal relationships between a given targeting effort and an observable outcome. In short, accurate analysis of bomb damage and targeting effectiveness is extremely difficult.

COMING UP IN THE NEXT INSTALLMENT…

The difficulty of measuring the effectiveness of bomber targeting (even with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight) forces us to look for other ways to think about targeting rather than seeking a single, optimal targeting approach. The next installment offers a suggestion about a more practical way to approach targeting and determine targeting priorities. Interestingly, the Allies actually followed this approach without knowing it at the time.